Foreword

As the last treatment of end-stage lung disease, lung transplantation can not only significantly prolong the survival time of patients, but also greatly improve the quality of life of patients. Over the past few decades, advances in surgical techniques, immunosuppressive drug, and post-transplant management have led to an explosion in lung transplantation worldwide. Between 2010 and 2018, there were nearly 34,000 lung transplants worldwide. Lung transplant candidates and recipients are a unique group; They are mostly characterized by multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogen colonization and infections, recurrent lung infections, high biomass of the respiratory microbiota (especially in the context of bronchiectasis lung disease) , multiple microbial infections, reduced mucociliary clearance, and immunosuppression.

Globally, ~ 15%-20% of lung transplant recipients (LTRs) have underlying cystic fibrosis (CF) , a unique group characterized by younger age of patients, and cystic fibrosis CF, multidrug-resistant pathogens have a higher rate of infection than other lung transplant recipients, a higher rate of antibiotic allergy, and a greater risk of infectious complications after transplantation.

A recent study revealed a significant increase in the number of lung transplants for the treatment of COVID-19-related acute respiratory distress syndrome during the 2019 novel coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic, and a significant increase in the number of lung transplants for the treatment of COVID-19-related acute respiratory distress syndrome during 2020-2022, 8.7% of lung transplants in the United States are for COVID-19-related acute respiratory distress syndrome. Many patients require long periods of mechanical ventilation and Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation before transplantation, which also increases their risk of nosocomial infections, in particular, those infections are caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, carbapenem-resistant acinetobacter Bowman and Aspergillus spp. Lung transplants are not appropriate for patients with uncontrolled lung or extrapulmonary infections, so lung transplant candidates need to resolve the infection before receiving a lung transplant.

Infectious complications are the leading cause of death in lung transplant recipients, accounting for approximately 30% of deaths in the first year after transplantation and approximately 20% thereafter. Common pathogens in the lung transplant setting include Pseudomonas aeruginosa, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Burkholderia cepacia, mycobacterium abscessus, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia and Achromobacter xylosoxidans. These microbes tend to be multidrug-resistant, so patients have very limited treatment options.

01

Clinical application of phage in lung transplantation

01

The phage therapy has been used in some lung transplant candidates and recipients, mainly against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections and atypical mycobacterial infections. Table 1 summarizes the published treatment cases, including 11 lung transplant recipients and 2 lung transplant candidates, by type of pathogen, type of infection, mode of administration, and clinical outcome. Overall, phage therapy was well tolerated and most patients were treated successfully. In 7 of the treated cases, the infection resolved clinically, four patients had clinical improvement (2 patients who had clinical improvement died of non-infection-related diseases during phage therapy and therefore could not assess the true outcome) .

表1 已发表的研究中涉及肺移植受者和候选者的噬菌体治疗案例总结

Note: clinical resolution: Resolution of symptoms at the end of treatment and negative target pathogen culture; clinical improvement: if symptoms improve but persist or recur with positive target bacteria culture; Clinical failures: such as lack of symptom improvement and persistent culture positivity.

02 Biodistribution of bacteriophages in vivo

In a report by Aslam et al (2019) , who administered phage therapy to three lung transplant recipients (LTR) , 1999-2019,2009-2019,2009,2009,2009,2009,2009,2009,2009, and 2009,2009,2009,2009,2009,2009,2009,2009,2009, these recipients had multidrug-resistant bacterial infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (patients 1 & 2) and Burkholderia (patient 3)[4] . Researchers in the patients with phage therapy at the same time, but also the patient’s respiratory phage biodistribution of specific assessment.

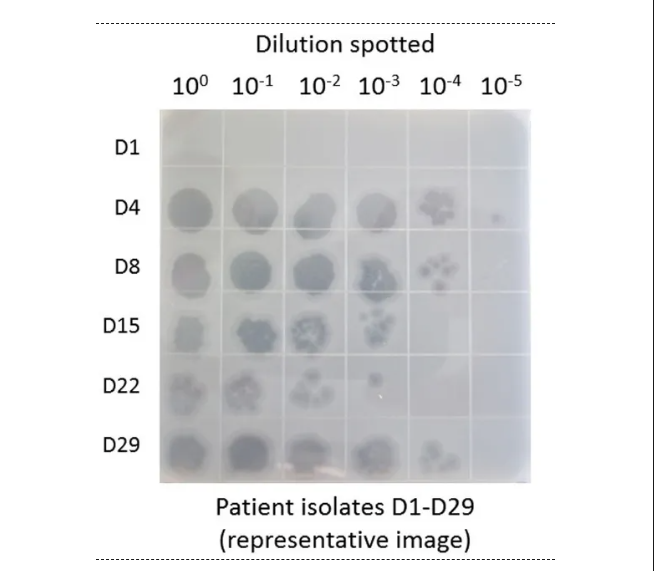

Patient 1 received two consecutive weeks of intravenous infusion (days 1-15) and nebulization (days 16-29) , both using the cocktail AB-PA01, in the first phase, this is a bacteriophage cocktail consisting of 4 strains of aeruginosa phage. As shown in Figure 1, no phages were detected in the alveolar lavage fluid before the initiation of phage therapy (D1) . Phage detection was approximately 4 × 10 ^ 7 PFU/ml in lavage samples obtained 3 days (D-4) after initiation of intravenous AB-PA01 treatment and on day 29(patients received nebulized AB-PA01 only the week before)(Figure 1) . These data suggest that both intravenous and aerosolized inhaled phages reach the lungs.

图1 患者1使用鸡尾酒AB-PA01治疗期间肺泡灌洗液中活性噬菌体的检测结果[1]。

03Safety monitoring of phage therapy

A 2022 systematic review of approximately 270 patients found that phage therapy are generally fairly safe, with an adverse event rate of 7% . In general, examination of baseline and weekly complete blood count, renal and liver function tests results, and inflammatory markers is recommended when patients are on phage therapy. Since bacteriophages are highly specific to their bacterial hosts, there is a theoretical risk that, in addition to being highly specific to their bacterial hosts, bacteriophages could also be used to treat bacterial hosts, that is, targeted elimination of specific bacteria in the respiratory biome may allow other potentially more pathogenic microorganisms to occupy this niche, leading to clinical deterioration. Therefore, close monitoring of vital capacity and forced expiratory volume in one second (Fev1.0) is also recommended for lung transplant candidates and recipients.

As with any new drug, anaphylactic reactions can occur with phage therapy, particularly in relation to excipients in the final product. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration recommends close monitoring within 3 hours of the first dose of phage therapy. Professor Saima Aslam from the University of California, San Diego said that at their clinic at the centre for innovative phage applications and treatments, when the first dose of phage is administered, an anaphylaxis kit is placed at the subject’s bedside, the kit contains antihistamines, epinephrine injections, H2 blockers, nebulized salbutamol and steroids (both oral and injectable) .

04

The latest clinical trial research in the field of lung diseases

04

As shown in Table 2, there are currently several early phase clinical trials focusing on patients with cystic fibrosis, but there is also one cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis trial that enrolled patients with P. aeruginosa colonization (Table 2) . In addition, an ongoing international registry of patients with CF and LTRs for complex biological colonization by Burkholderia, which is collecting bacterial isolates from enrolled patients, has been developed and is currently available in the United States, these isolates were used to develop a lytic phage library that was eventually used in preliminary clinical trials.

The clinical trials mentioned above assess the effectiveness of phage therapy by monitoring a variety of end-point metrics, which can be used to assess the efficacy of phage therapy, its indicators include a reduction in the amount of microbiota in sputum, changes in the lung (its function is assessed by forced expiratory volume in 1 second) , changes in the composition of the airway microbiome, and clinical outcomes (such as changes in symptoms and hospitalizations) , and close monitoring of adverse events. At the same time, these clinical trials will also evaluate phage dynamics and pharmacodynamics as well as the development of drug resistance and serum neutralization.

表2 正在进行的评估噬菌体治疗在肺部疾病中作用的临床试验

Summary

Lung transplant candidates and recipients bear the burden of disease from multidrug-resistant pathogens, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Achromobacter xylosoxidans, Mycobacterium abscessus, and Mycobacterium cepacia, among others, and are more susceptible to infection with these pathogens, they not only directly cause disease and death, but also affect the course of treatment and post-transplant outcomes, including the development of chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD) . Phages, as a novel and highly targeted tool, can be applied in lung transplantation settings in a variety of ways, thereby influencing all these outcomes.

References

1.Chambers DC, Perch M, Zuckermann A, et al. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty-eighth adult lung transplantation report—2021; focus on recipient characteristics. J Heart Lung Transplant 2021; 40:1060–72.

2. Okumura K, Jyothula S, Kaleekal T, Dhand A. 1-year outcomes of lung transplantation for coronavirus disease 2019–associated end-stage lung disease in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76:2140–7.

3. Saima Aslam. Phage Therapy in Lung Transplantation: Current Status and Future Possibilities. Clin Infect Dis 2023 Nov 2;77(Supplement_5):S416-S422.

4. Aslam S, Courtwright AM, Koval C, et al. Early clinical experience of bacteriophage therapy in 3 lung transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2019; 19:2631–9.

5. Uyttebroek S, Chen B, Onsea J, et al. Safety and efficacy of phage therapy in difficult-to-treat infections: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 2022; 22: e208-20.